Let Them Eat Cake! – Understanding Effective STEM Teaching in a Global Context

A common question that comes up while leading educators in STEM professional learning is “What does STEM mean?” Many would answer this by defining each of the letters, Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, leaving the teacher to believe this acronym just puts all of the scientific and technical classes taught in a school into one basket.

However, those of us involved in the STEM movement know it is much greater than that. When done right, the power of STEM learning involves teaching problem-solving and giving learners a lot of practice using knowledge from different disciplines to solve real-world, problems. This active form of STEM allows learners to formalize their own problem-solving paradigm, which they can rely on for the rest of their lives.

It is important for those involved in developing strong STEM learning programs to have a common understanding of what is meant by STEM and how one’s goals reflect this philosophy. This is never truer than when you are helping leaders of a country decide how they will develop a STEM learning program to prepare youth for the modern world.

Dr. Katherine Bihr and I got to understand this first-hand when we had the opportunity to join Jan Morrison, Founder, President and Managing Partner of the Teaching Institute for Excellence in STEM (TIES) and her team, as they led a training with educators and professional learning professionals from Carasso Science Park in Be’er Sheva, Israel.

The goal of this training was to help educators understand the power of STEM to equip students with skills in problem-solving and to empower them to bring these skills to bear in the real, modern world. So how do you explain this integrated definition of STEM to a group of educators that are used to a siloed approach to science and technical teaching, especially when English is not their first language? Jan did it masterfully using a layered cake analogy.

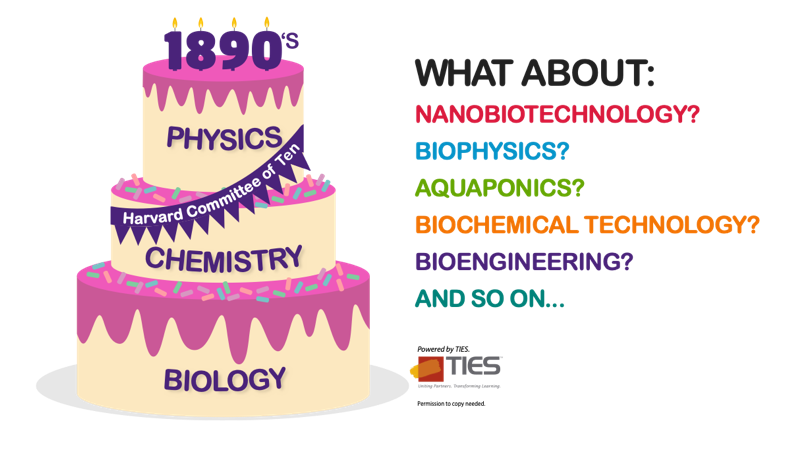

As Jan explained to the group, much of the teaching of science in schools is a product of the Committee of Ten recommendations, a working group of educators in 1892 who made suggestions of how to standardize American high school curriculum. These recommendations were interpreted as a call for the teaching of English, Mathematics and History to every student in every academic year and the teaching of Biology, Chemistry and Physics during ascending high school years. While this practice standardized what students were learning in American schools, and later shared with the rest of the world, it led to siloed, disconnected curricula that do not prepare students for the realities of post-secondary education and the workforce of the 21st century.

“Imagine if you will,” said Jan, “a layer cake that has Biology, Chemistry and Physics as its layers. These layers are distinct from each other, but when you go to eat the cake, you will slice between the layers, pulling different pieces from each layer to form a complete slice.”

Even though the cake is made as separate layers, the only way to slice it is to take a bit from each layer. This is exactly, as Jan explained, how we should teach STEM. Teach students the steps of problem-solving and turn them loose on the problems of the world, helping them use knowledge from all disciplines to arrive at novel solutions. This training continued with lots of great practical and philosophical discussions on the teaching of STEM, but the layered cake analogy gave us all a great common understanding that we could continue to go back to as we workshopped best practices in STEM teaching.

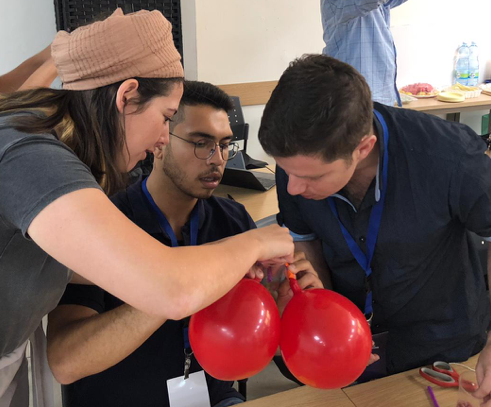

For example, Kathy and I led a STEM challenge based on the attempted moon landing of the Beresheet moon lander attempted by SpaceIL, a private, non-profit space organization in Israel. Given this mission was successful in all of its objectives, except for landing on the moon – communication errors at the last moments led to the lander crashing – it is a great example of failing forward.

Educators in the training were to use provided supplies to build a new lander design that would travel to the moon and land. These “landers” were to successfully travel across a length of string powered only by a balloon. This activity was meant to help participants in the training see a practical example of our STEM learning approach – understand the problem, make a plan to solve the problem and use, or gain, knowledge from different disciplines to try and try again until a solution was reached.

In only 30 minutes, most groups did arrive on successful, unique solutions. A large takeaway for me from this experience is that educators can find commonalities in our shared experiences, even when we are from different countries, and that we can make education better by a concerted, sustained movement of teachers working together to share best practices that work.

This was one of TGR EDU: Global’s first trips to understand teacher professional learning in an international context, as we prepare to bring our U.S. educator-tested programs from TGR EDU: Create to other countries in the world. This was a fantastic opportunity to learn with Jan Morrison and her team at TIES and to truly understand the opportunities and challenges that face Israeli educators as they take these first steps to crafting a modern STEM program for the youth of their country. We truly were able to get a great sense of the challenges and rewards of this work and can apply these lessons to other countries we will partner with during our expansion.

While there is still much to be done to successfully prepare teachers and students to embark on integrated STEM programming that prepares them for the modern workforce – the charge is clear. Let them eat cake!

Redefining what it means to be a champion.